By James Retherford [convicted pie thrower]

Originally published in The Rag Blog, Austin, TX, August 19, 2008

Comedian Ritch Schydner used to perform frequently at Austin’s Comedy Workshop, and my spouse Cindy and I developed a warm friendship with him and his Austin-born wife. Early on,

I noticed that Ritch’s comic schtick was unique; he did not make jokes about individuals or classes of people, except himself and the class he represented — i.e., clueless white guys. Yeah, he told wife and mother-in-law jokes, but he himself was the punchline of these routines. No off-color sexual jokes. No potty-mouth humor. No ethnic jokes. No vulgar class jokes. In short, none of the stuff I had grown accustomed to seeing on the Comedy Workshop stage. One night backstage as we tossed down a couple tequila shots after his show, I asked Ritch about it. His reply, as I remember it, was something like this:

“It doesn’t take talent to exploit other people in order to get a cheap laugh. I think it is lazy, and I also think it is wrong.”

Obama and The Onion : Reflections on the Uses of Satire

I recently chuckled at a satirical piece I found at The Onion’s website and reposted it here on The Rag Blog with barely a second thought. The story, “Obama’s Hillbilly Half-Brother Threatening To Derail Campaign,” stirred up a tempest. My co-editor Richard Jehn found it especially tasteless and pulled the story until we could discuss it. Though I’m a great fan of hard-hitting satire and consider no one above a bit of good-natured fun, I tended on reflection to agree with Richard and we left The Onion’s article off the blog. But I did pass it around for reaction.

Well, as often happens in our little corner of the internet, the whole affair inspired a discussion that has been fun and insightful. And best of all, Jim Retherford wrote the following rather eloquent reflection that is well worth a read!

Below Jim’s thoughtful take, I’ve included a bunch of posts from Rag Blog readers and friends – and I definitely urge you to read them. And, by the way, here’s a link to The Onion’s satirical piece – which I just noticed is still number one on their “hit” list.

Thorne Dreyer, editor, The Rag Blog

Photo from controversial satirical article in The Onion: Cooter Obama chases pig on Capitol lawn. Photo © Copyright 2008, Onion, Inc.

Ritch Schydner — clueless white guy humor

Unlike Mike Klonsky’s and Carl Davidson’s thoughtful remarks, I simply dismissed the Onion piece as lazy and “not funny” and did not parse it further. As far as I’m concerned, “not funny” itself is the rimshot-punctuated death knell of satirical writing. It means whatever humor was intended missed the mark.

Badda-bing!

Why does the Onion piece miss the mark? As one with working-class redneck/hillbilly ancestral roots spread from Texas through the Smoky Mountains into rural Indiana, I find Appalachian culture and people a force to be celebrated, not mocked — especially not to be mocked by opportunistically “using” another historically marginalized and oppressed racial/cultural group such as African-Americans.

Not funny.

I have never watched a single episode of Beverly Hillbillies. It ain’t funny. There’s nothing funny about the brave men and women who stood up to the capitalist oligarchs at Paint Creek, Cabin Creek, Matewan, Blair Mountain, “Bloody” Harlan and Bell County, and Ludlow. These folks are heroes in my book.

Nothing funny about what Peter Rowan calls that “high lonesome sound” of Jean Ritchey, the Stanley Brothers, the Monroe Brothers, Hazel Dickens, Jim Garland, Sarah Gunning, Aunt Molly Jackson, the Carter Family, Flatt and Scruggs, Jim and Jesse, Charlie Poole, Doc Watson, Merle Travis, and many many many more.

Nothing funny about the art of Grandma Moses either … or the near-anonymous master whittlers and quilters of the southland’s hills and hollers.

There was plenty of funny about Minnie Pearl. Cousin Minnie’s hillbilly humor brings us to a very important observation, to wit:

Hillbillies — and African-Americans and Mexicans and Poles and Irish and women and men and gays and very tall people and very short people — have unlimited license to laugh at themselves. Black comics tell nigger jokes, gay comics tell faggot jokes, Ritch Schydner tells “clueless white guy” jokes, and the members of their constituent groups ROTFL.

Long-oppressed groups have risen up to reclaim the words that once were used to inflict pain and self-loathing and turn the language of their oppressors upside down, inside out, and up against the wall.

But in a world where oppression is a systemic disease, the language license is not transferable to any other class or group.

Why not?

Within these groups, rap, banter, trash talk, and humor is egalitarian. No one is “better” than anyone else. To riff on your friend’s po’ mamma is to riff on your own po’ mamma.

But when humor is directed from one class at another, it is no longer egalitarian. It becomes hierarchical — and oppressive — as a performer representing the attitudes of a particular group or class invites the audience to join in the act of making fun of a “lesser” group or class. Moral, cultural, sexual, intellectual, racial, and/or class superiority emerges as the fundament of the routine, and targets of moral, cultural, sexual, intellectual, racial, and/or class inferiority are lined up by the enterprising jokester for the comic “kill.” Those words (like the n-word) reassume their denigrating meanings.

I would further argue that derisive and demeaning “humor” directed at any marginalized or oppressed individual, group, or class can be — and is often — construed as a subtle form of violence, an attack on the very soul of culture, on the right of the individual, group, or class to be. As progressives, we should understand this by now.

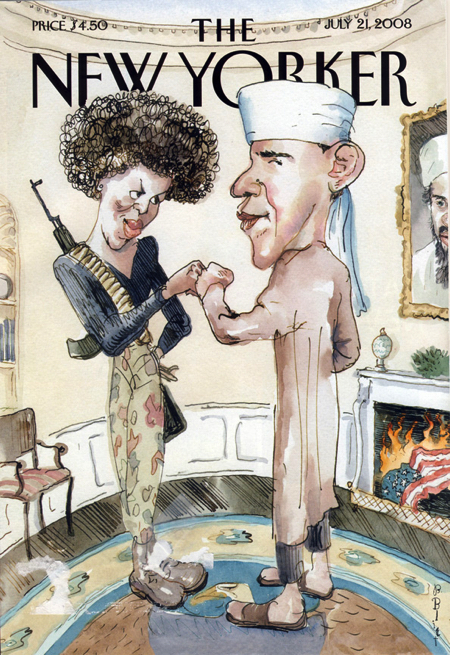

Some may argue that “not funny” does not necessarily translate into “offensive,” but this is a false dichotomy and begs the basic question of class and power. I didn’t find characterizations of Jimmy Carter’s and Bill Clinton’s kinfolk funny either; I thought the revelations about Billy and Roger made the candidates more real. Rather I am reminded of the infamous recent New Yorker cover and of the white middle-class liberal intellectuals who, officiously incredulous by the uproar, declared, “If you don’t find this funny, something is wrong with you.”

So what IS wrong with me?

First of all, I was born into poor white farming family and didn’t have running water — except for the creek (crick) that ran through the woods behind the back pasture — or indoor “facilities” until I was in the eighth grade.

My father was a tenant farmer who would disappear for days at a time on drinking and womanizing sprees and was abusive when he was at home. My father’s family — with a few exceptions — boasted of their lineage to ex-Confederates and horse thieves, and my father proved worthy of his bloodlines when one drunken night he came home with a loaded shotgun intent on killing my mom, my younger brother, and myself. He ended up in jail and then in a mental institution where he was given shock treatments.

My mother was an orphan who worked her way to a teaching degree at Indiana University. She taught in a small country school during the winter months and kept chickens, tended a very big garden, and worked in an aluminum factory in the summer to keep food on the table and clothes on our backs.

As an orphan, however, she was not aware until late in her lifetime that her great-grandfather and great-great-grandfather were two of America’s most militant abolitionist and women’s rights statesmen of the first half of the 19th century. One was a two-time vice-presidential candidate — and both were founding leaders of the original GOP. (My grandson bears their names, Julian Giddings Retherford.)

Second, for several months in 1974 I lived “underground” in the back of a holler in Calhoun County, WV, with my infant son Jesse James. While there I spent a lot of time down the crick visiting a retired coal miner and listening to hair-raising stories about the West Virginia coal wars and the rise of the United Mineworkers Union of American (UMW).

Every weekend a nearby community hosted a “sing,” a potluck-and-music event at which family musical groups from all over the nearby counties fiddled and sang from a makeshift stage. The spirit of communal sharing among the hill folk and the transplanted hippies was contagious and memorable, and I still get misty-eyed as I recall one lovely young local lass (aged 14 or 15) singing lilting tear-stained a cappella ballads plucked straight from the 15th-16th century Scottish highlands.

Ah, that high lonesome sound.

So what else is wrong with me? In August 1967 I had the remarkable opportunity to hear SNCC spokesperson James Forman tell a room full of white middle-class liberal intellectuals sporting “I Am Not Racist” buttons just how racist they (we) really were. The place was Chicago’s Palmer House ballroom at the infamous Conference on New Politics at a juncture when the emerging Black Power movement increasingly was at loggerheads with white paternalism in the civil rights struggle (and, I also should add, COINTELPRO was in full swing). Forman told the smug and testy white members of the audience [my paraphrase follows]:

“You say you aren’t racists. You say you have overcome your racism.

“You’re wrong. You ALL are racists! Each and every one of you is racist to the bone. …

“I’m not saying this to you in anger. I’m just stating fact. And the fact is that white people

in America are racists. I also recognize that white people can’t help it. Your parents and

your grandparents were born and raised in a racist society. You were born and raised in a

racist society. You are schooled in racist schools. You get all of your news and information

from racist media. You are bombarded by racist advertising images. So the question isn’t

whether or not you are racist. The question is: When are you going to acknowledge your

own racism? And then what are you going to do in order to understand and eliminate it?”

Forman further noted how white liberals, having declared themselves “beyond racism,” always seem to reserve for themselves the moral authority to arbitrate matters of racial acceptability. (To me, the Geraldine Ferraro flap was a classic example of what Forman was talking about).

Challenging white liberals to cease such paternalistic practices, Forman asserted that only victims of race [or class or gender] oppression are qualified to judge whether an image or action directed against them is offensive and/or oppressive.

His parting words challenged white middle-class liberal intellectuals to learn how to accept leadership from the victims of race and class oppression, the very people on whose behalf white liberals joined the movement, the very people suffering under the yoke of bigotry and intolerance.

(Four decades later, Forman’s admonishment continues to strike me as extraordinarily measured and reasonable. And four decades later, white middle-class liberals continue to claim the moral authority to stand in judgment over matters of race and class, to arbitrate over what is funny and what is not ... not to mention, what is just and what is not.)

2008 New Yorker cover: Upper East Side humor?

So what IS wrong with me?

My own life and work certainly has not been without yucks.

How many people show up to testify before a federal grand jury of the Weather Underground’s bombing of the U.S. Capitol dressed like King Kong? Hey, I heard they were looking for urban gorillas.

Or silence a world-class right-wing windbag who was disrupting an SDS meeting with a bellicose pro-war rant by wrapping him up in an American flag and pulling him off the stage?

Or get busted for throwing a pie in the face of a nationally recognized adversary of free speech?

Like Ritch Schydner, I eschew the “easy” laugh, the lampoon of the socially marginalized and oppressed individual or class.

On the other hand, I do NOT subscribe to the idea that humor cannot set its sights on any group or class.

Instead I align with the free-for-all tradition of dada, the surrealists, the Keystone Kops (“pie-throwing as a fine, wish-fulfilling, universal idea,” Mack Sennett famously once said, “especially in the face of authority”), the Situationists, the Provos, the Motherfuckers, the Yippies, and the Daily Show.

I see humor as a weapon to be wielded as scalpel or bludgeon — or lemon meringue pie — against oppressors, i.e., the ruling class and its oiligarchy. As Jay Jurie suggests, “Let’s lampoon the hell out of the rich and powerful.”

But as history — and my rap sheet — shows, this is not the “easy” laugh.

Meanwhile this discussion provides an excellent opportunity for each of us to take account of where we stand in regard to our lifelong struggles to understand and eliminate the vestiges of our own racism and classism (and, among us of the male gender, our sexism).

Any open-minded, non-defensive survey of the U.S. cultural map in the first decade of the

21st century will, I think, show us that we still have a long long long way to go to meet James Forman’s clarior call of four decades ago and the many subsequent challenges that have followed.

In 1967 Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee executive secretary James Forman had sound advice

for white liberals, but a half century later there is little evidence that anyone listened?